On a trip to New York City about 10 years ago I stopped at The Old Print Shop near Gramercy Park to look at some antique maps. I had just started my collection and was still looking for some unique European-made maps of China.

The shopkeepers told me in recent years wealthy Chinese buyers were buying these old European-designed maps and bringing them back their homeland. They hadn’t yet developed a specialty for these in the shop as they primarily focused on maps of New York and the East Coast.

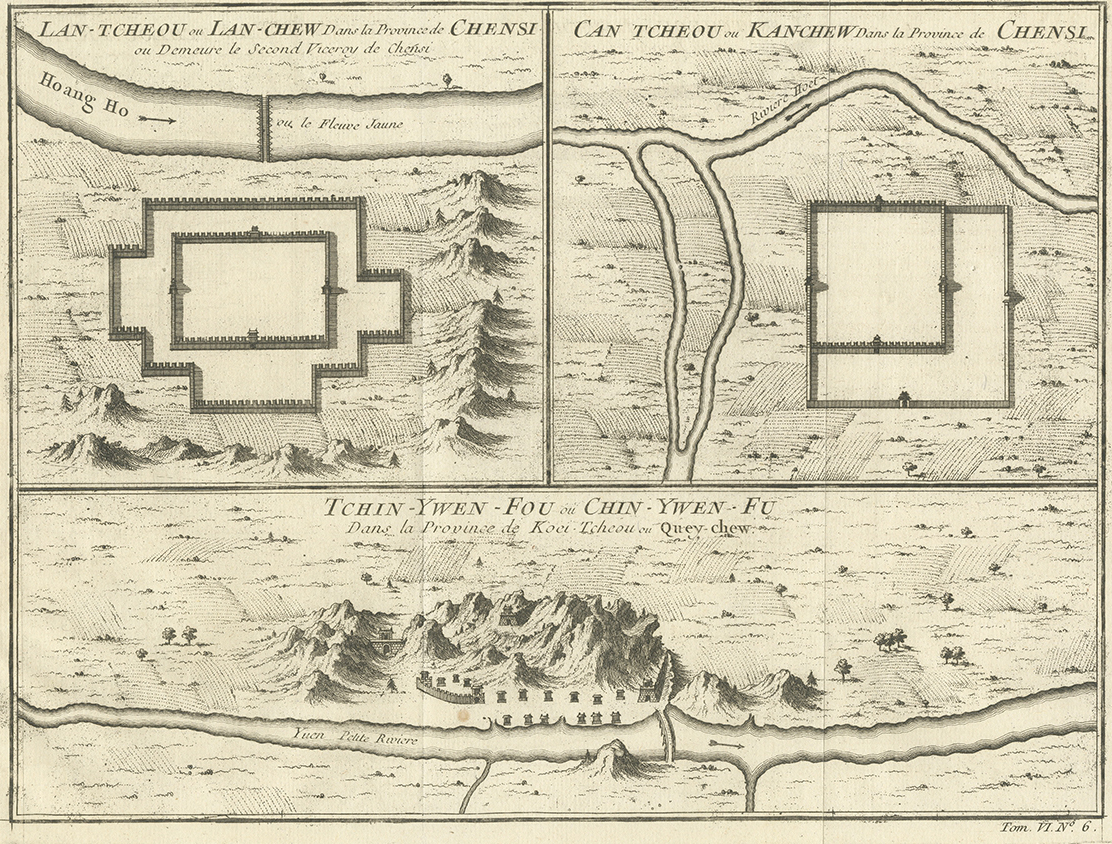

After combing through the collection a while I settled on a unique three panel map from the mid-1700s. It would be the oldest map in my collection. While not particularly rare, the idea of owning a map older than the country I’m from excited me more than enough to spent the $100 on a small, near A4 size page block print map. The map in question was pulled from from an edition of Abbé Prévost d’Exiles “Histoire générale des voyages” (1747-1767). The map can be found on page 457 of the Seventh Volume in a section about Shaanxi Province. The map was created by French geographer JN Bellin and engraved by Dutch draughtsman Jacobus van der Schley.

Most published maps at this time were not designed by people that had on-the-ground experience, but rather compiled from data, sketches and surveys from Jesuits living in China. In fact, Bellin himself created more than 50 maps from around the world for this multi-volume book.

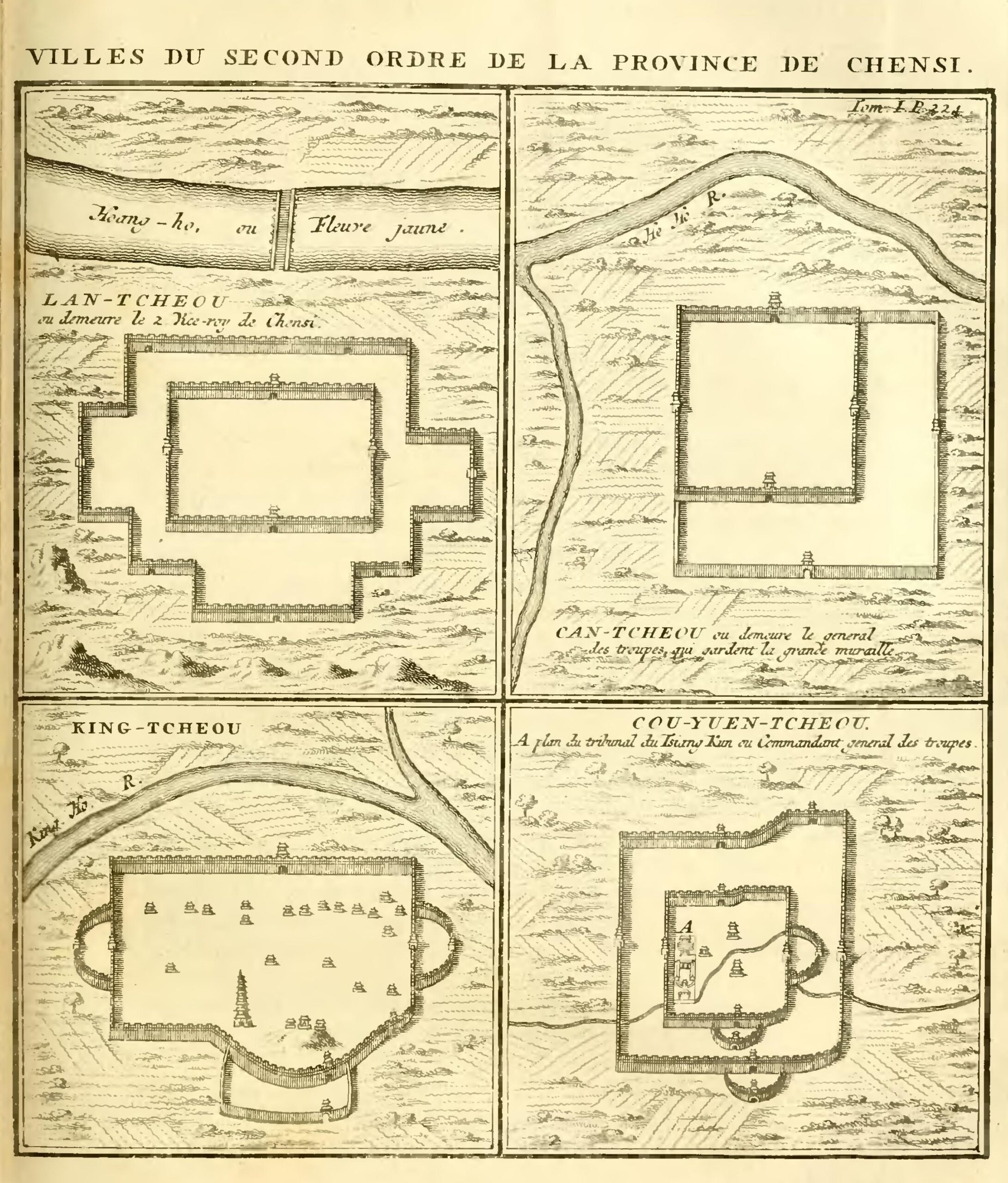

However, upon doing some reverse image searches in Google, it appears that these maps were heavily borrowed from Jean-Baptiste Du Halde’s 1736 book Description de la Chine (published in English as “The General History of China”). Many of the maps in this book were created by cartographer-to-the-king, Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville. Du Halde was a French Jesuit historian that specialized in China (despite never visiting himself) and a major reference point for the time period. Du Halde and d’Anville’s work are cited in the book, but the maps are near-exact copies. Here are the maps from his book for comparison:

What drew my attention to this map in particular was the peculiar use of blank space. While sea monsters and sirens often filled the vastness of the ocean on maps, Bellin’s background as a hydrographer lent a less-fanciful perspective to the open sea. Many of his maps have lots of blank space that give it a perceptively modern touch. Courage in the face of horror vacui drew my attention to the white space of the city walls and fortifications.

After bringing the maps back to Austin from New York and getting it framed I had to put some effort into determining all of the locations displayed. While there was a historical system used by missionaries to romanize Chinese place names, they don’t often translate well to modern pinyin. The top two maps were easy enough to discern given their historical importance, but the third (bottom) map required the most work. Most of the my research laid dormant in a Google Chrome bookmark folder for more than half a decade.

Lanzhou 兰州 (Top Left)

Romanized as “Lan-Tcheou” or “”Lan-Chew”, Lanzhou is described on the map as part of Chensi (Shaanxi) province and displays the old fortified city walls with lots of empty space. An additional description in French describes the city as “…where the Second Viceroy of Chensi lives” (ou là où vit le deuxième vice-roi de Chensi).

While I never visited Lanzhou during my time living in China, the Muslim Hui population from this area were people I interacted with frequently when I lived in Shanghai. Whether it be from Lanzhou Lamian or my roommate Peter tutoring a family English.

At the start of the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912), Lanzhou was made the capital of the newly-formed Gansu province. However, it was still under the rule of the Viceroy of Shaan-Gan (according to Wikipedia, officially the Governor-General of Shaanxi, Gansu and Other Local Areas, in Charge of Military Affairs, Food and Wages, Tea and Horses and Governor Affairs), so it makes sense that the map incorrectly shows Lanzhou as part of Shaanxi province almost 100 years after the change.

The map’s orientation shows South-as-up as the old fortress is on the southern bank. However the Yellow River (named as Hoang Ho) is shown to be flowing left-to-right, which would be incorrectly East-to-West.

There isn’t much to the old Silk Road city on this map, but I find the detailed rendering of the surrounding mountains to be a counterbalance to the empty city map. While the mountain the city is named after isn’t prominent (GaoLanShan), I would say that it gives the impression of its 5,000 feet (1,500 meter) urban elevation on the outer edges of the Tibetan Plateau.

Most Silk Road maps help me mentally connect my maps of China to my modern Mongolia map I purchased in 2010. It’s easy to imagine people stopping here on bactrian camels before heading to further East within China or up toward Karakorum.

Prevost describes in the book (via Google Translate), “Although Lan-cheu is only a city of fertile rank, and depends on Kyang-hyang-fu, it is the capital of Iton and the governor’s residence, because being near the Great Wall and the principal gates of the West, one can easily send from there the necessary aid to the troops who defend the entrance to the Empire…Lan-cheu does not pass for a rich city. Between the strong Towns of this Province which are devoted to the defense of the Great Wall, we count Si-ning, To-pa, Ken-tan (m), Kan-cheu, Lyang-cheu, Ning-bya-wey & Yu-ling-wey. All these Places are guarded by Troops, under the command of as many General Officers; but the Generaliffime(?) is the one who lodges in Kan-cheu, a confidable Town, like that of So-cheu.”

Ganzhou 甘州 (Top Right)

Some 310 miles (500 kilometers) to the southeast of Lanzhou is the prefecture city of Zhangye. This Gansu province city was known by two names over hundreds of years, Ganzhou and Zhangye. It wasn’t until 1992 that the Chinese government uniformly enshrined its name as Zhangye, leaving the ancient city, now a district within the city, to be called Ganzhou.

Without going too much into the administrative organization of China throughout its history, Zhangye/Gansu changed administrative organization many times. There is a long blog post from the Zhangye Municipal People’s Government (Chinese only) on the origins of the city’s names. The post mentions that for hundreds of years the government changed the name and municipal status of Ganzhou/Zhangye as many as five times over the course of 300 years (before 1000 AD). Today, the city is known for the nearby Zhangye Danxia Geopark and its colorful sandstone mountains.

As with the previous map, this one also labels Ganzhou as part of Shaanxi province (Chensi) even though by the time of publishing it was brought under Gansu province. The Kan-Chow romanization often pointed me incorrectly to the Jiangxi Province city of Ganzhou (赣州) more than a thousand miles away. The name “Gansu” originates as a portmanteau of Ganzhou and Suzhou (肃州 – not the one Jiangsu Province). From a modern perspective both romanized place names for the map are incorrect, which made finding its modern location rather difficult.

But enough about the city’s name: this map shows Ganzhou, oriented in a North Western upwards fashion, to show the Heihe River at the top, with its ancient city walls in focus. A small canal-like creek is shown on the left-hand side, but is not viewable on satellite maps anymore (likely diverted for the irrigation and farming in that area now). Like Lanzhou, Ganzhou was part of the oasis-strewn Hexi Corridor of the Silk Road, and was protected with an inner city wall and an outer city wall. The detail of the city is missing in the city walls, just like the others.

Portions of the city wall (primarily from the Ming Dynasty) still exist in Zhangye and can be seen on Baidu Maps Street View. The high desert of Ganzhou isn’t accurately represented in the map, but it does portray the sense of “otherness from Europe”, which was often the goal of maps at the time. My aesthetic enjoyment of the white space and its relation to the Silk Road are more interesting than any attempt at accuracy of “place.”

Zhenyuan 镇远县 (Bottom)

The bottom half probably took the most work of identifying when I first purchased this print many years ago. The romanization “Tchin-Ywen-Fou” yielded zero results for many years and required me to manually follow along the Yuan River (shown as Yuen Petite Riviere) until I found a city or village that matched its cartographic representation by using Baidu Maps. A dense urban area surrounded by tall limestone mountains along the river was a dead giveaway. Nothing else like that exists in along the Yuan River. It was definitely Zhenyuan. When repeated slowly, “Tchin-Ywen” and “Zhenyuan” sound exactly alike.

How did I not find this for so long? In Du Halde/D’Anville’s map, the city was romanized as “Tchin-Yuen-Fou”, just different enough that I wasn’t able to accurately find it for a long time. It was frustrating to know I was so close (and that Google couldn’t associate the place name), and that Bellin didn’t copy Du Halde accurately enough!

Currently, Zhenyuan Old Town (the area on the map) is part of Zhenyuan County in the Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture. With a population of 200,0000, it’s a small town by modern Chinese standards. There isn’t an obvious connection between the regions of the previous two maps. Guizhou doesn’t have a direct connection to the Silk Road, the Yuan River doesn’t connect to the Heihe or Yellow Rivers, and there aren’t any threads connecting them culturally, or in the source text — it’s also 2,100 KM or 1,300 miles from Gansu province by car.

This map clearly has the most detail of the others (as does the source from Du Halde/D’Anville), but does make it appear that Zhenyuan to be a small enclave near the mountains. While the other maps accurately portray relatively flat areas surrounded by a larger, more distant mountain range, Zhenyuan appears as if the mountains surrounding it are standing on their own on a plain. In reality, the whole region is mountainous and goes on for many miles.

The original Du Halde/D’Anville map of Zhenyuan is a collection of three Guizhou cities, and Ganzhou and Lanzhou are part of four maps on a page showing other Shaanxi (Chensi) province cities.

The only connection are the notable non-Han populations in both provinces. The map is at the end of the encyclopedia’s section on Shaanxi province that dovetails into Sichuan province (which isn’t close to Guizhou, either). There aren’t many maps in this volume, and many of them aren’t placed in the sections discussed. In a section on Yunnan Province, two maps of Longguan and Zhengding in Hebei Province are shown. Very likely, the maps didn’t have direct relation to the places shown.

Of course, these are nitpicks to things that don’t detract from my overall enjoyment of the maps.

To the elites, clergymen and academics that would have owned this encyclopedia many hundreds of years ago, China was a fairly abstract place. Most people only interacted porcelain and other goods imported from there. Any illumination on the people or places were novel information to understanding the wider world. The collection of these three maps on a single page succeeded in delivering information about a far away land, even if their placement doesn’t make sense to our modern eyes and sense of Geography.

Overall, it’s exciting to own such a piece of history that provides the context and knowledge of the time. I hope I’ll be able to find more like these in the future.

Isn’t it “Generalissime” with a long S?

Very possible! I had to machine translate this.