Part 2: Perceptions and Success

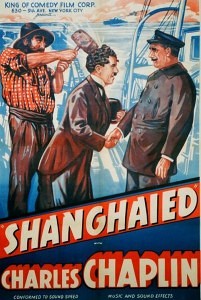

For many years in the West, association with the word “Shanghai” usually revolved around sailors being coerced into slavery-like work conditions on the high seas. A person being “shanghaied” was a person that was given a raw deal, or whisked away somewhere (or into a job) under dubious pretenses. This became one of the most common associations with a former colonial boomtown.

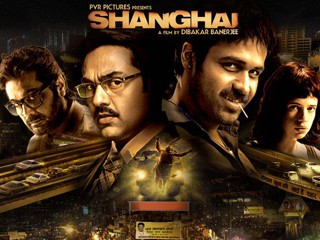

However, China’s explosive growth has changed the meaning of Shanghai to Westerners and people in other countries. In 2012, Twitter exploded over the use of the hashtag “#Shanghai.” However, this trend was for different reasons than one would expect. In India, a Bollywoood movie entitled “Shanghai” had just been released. The movie was not shot in China’s second city, nor included any Chinese actors. Shanghai,” a political thriller, told the story of a small city in India being redeveloped into “the new Shanghai,” a glistening metropolis ordered by government decree and at the built by the poor and downtrodden.

The success and rapid pace of China’s growth began to mean something else to outsiders. Shanghai, with its “three brothers” skyscrapers and glittering lights mean power, success and a little fear. Without the aid of the Chinese government, the Indian people were able to freely associate China’s growth and political power with success. While the association of Shanghai for Indians may contain some critiques of large and powerful central governments, the end result ultimately benefits China. The world’s second largest country in population sees China as a powerful force. It is imperfect, and not without criticism, but it’s the result of successful soft power nonetheless.

Instead of allowing for open (no matter how imperfect) representations of China to disseminate allow the world to see China’s values and economic prowess. The yearning for global recognition has resulted in a pursuit for the world to see China in only one approved form. However, there is no one-way to understand the ideas and culture of an entire country. Each country has many facets, good and bad, that allows people from all corners of the world to accept. When media, culture and ideas are spread around the world naturally, its recipients are able to interpret their own meanings and apply it to the country. That’s when, as Nye describes, you will be able to coopt others instead of coercing them.

“Hallyu,” or the Korean Wave, is an example of South Korea to produce cultural artifacts that the rest of the world can consume. Korea’s cultural output is not about its “Korean-ness,” it’s about creating an easy to consume product. The Korean media halo sometime allows foreigners to become interested in Korean food and sometimes even the Korean language. This positively affects the way people see South Korea. For example, the global popularity of the song “Gangnam Style” by PSY would never pass muster in China under the pen of a local propaganda officer. PSY’s criticisms of the opulent Seoul neighborhood doesn’t embarrass or make South Korea look bad. Instead, PSY’s success makes the country proud, despite the message.

Korea’s perspective is something for China to strive for. It harkens back to the old show business maxim, “there’s no such thing as bad publicity.”