In November 2015 I took the chance to go back to Shanghai and visit China for the first time since moving from there back to the United States in the latter half of 2013.

I left when the eyes of the world were on the country. Watching it’s economy struggle to convert from a manufacturing-based economy to a service industry back home has been interesting. The main reason I went back to Shanghai (after visiting Taiwan) was to get a pulse of the Internet there. I wanted to talk with business owners, locals and foreigners living there to see how the Internet has been changing along with China’s growth.

When I lived in China WeChat was my lifeline between my friends across different mobile platforms. The messaging app is a mix of Facebook, Instagram, Venmo, WhatsApp and Twitter all rolled into one. Businesses use it for marketing, people use it to share photos, voice messages, engage in group chats and I still use it today to talk to people back in the Middle Kingdom.

It was the easiest way for me to get into the mind of my Chinese colleagues and friends. Tencent, the Shenzhen-based tech company that developed WeChat, was extremely smart about its development. WeChat first started as Weixin (微信) for the Chinese market in 2011. At first, it was a Chinese-language clone of WhatsApp. As China’s wealth increased, most newly-monied Chinese bought a smartphone before buying a tablet or laptop. With some Android-based smartphones as cheap as 1000 yuan ($160 USD), the wider web became more readily available.

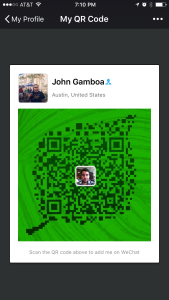

After some time, though, Tencent saw a potential in developing tech markets and then released multiple localized versions on the Weixin platform. To Anglophones, Weixin in English became known as WeChat. Hooked into the Wexin platform, I could easily share photos, links and messages and voice messages with Chinese friends using the Chinese-language Weixin app. While virtually the same, their marketing in different places of the world was quite different. You can pay electric bills, book bus rides, check pollution levels, check traffic, send money to friends, connect with local businesses, read QR codes (which are still in wide use in China) and even order food.

While many of those features were added to WeChat during my time living there, it became apparent while visiting that WeChat had become the Walled Garden du jour for the Chinese Web. When I was on the subway or taking a taxi to meet friends, WeChat seemed to be the only way anyone was communicating to one another. WeChat’s growth has been astronomical and it’s gaining a lot of attention for it.

As Facebook is still blocked or relegated to use of those with VPNs, WeChat fills the perfect void for those in China who live on mobile and don’t want to share publicly like Weibo (a micoblogging platfrom akin to Twitter). With all its features behind its platform (patrolled by the in-house censors at Tencent) WeChat becomes the best way to lock into the Chinese zeitgeist.

While you’re likely not going to be censored in direct person-to-person messages in WeChat, it’s important to always consider your correspondence with people compromised. Until recently, some major Chinese messaging services had End-User License Agreements (EULA) in which any works transmitted using their system became property of the messaging company. Anything you publicly post to friends, or through business or official accounts could be blocked if deemed sensitive by government officials or company censors.

The government likes it, the people like it, and its a growing Chinese brand. It’s on the fast-track to being a big star. So, while being back in China, it was the best –if not only way– to reconnect to all my friends and plan meetings with new ones. While other platforms like Sina Weibo, QQ and Renren are still there, WeChat is China’s tech star with global ambitions.

With all the concern from China’s leadership about the country’s reliance on foreign technology (Google especially) for mobile platforms, Tencent is poised to create an entire mobile ecosystem around a single piece of hardware if it plays its cards right. An entire mobile OS or smartphone dedicated to WeChat features would instantly win the hearts of people and the Politburo.

What does this all mean for WordPress?

Just like the push to mobile/responsive design in the past few years in WordPress, so will be the attention needed for Chinese methods of using the Web. As developers start to design webpages with mobile in mind, the WeChat User Agent will be something to look out for. While many people are wary of traffic to their sites from China, the micromessenger user agent is a sign that your site is being shared or read via WeChat’s platform. If you’re able to keep an eye on the changes for WeChat, or see an increase in users reading your content from WeChat, you’ll be able to take advantage of a growing potential user base